The NHBPA has 30 affiliates across the United States and Canada, including: Alabama; Arizona; Arkansas; Canada; Charles Town, West Virginia; Colorado; Finger Lakes, New York; Florida; Idaho; Illinois; Indiana; Iowa; Kentucky; Louisiana; Michigan; Minnesota; Montana; Mountaineer Park, West Virginia; Nebraska; New England; New Mexico; Ohio; Oklahoma; Ontario; Oregon; Pennsylvania; Tampa Bay, Florida; Texas; Virginia; and Washington.

The NHBPA strongly takes issue with misstatements regarding the alleged misuse of racing medication in the horse racing industry. A feature article in the March 25, 2012 New York Times (“NYT”), “Mangled Horses, Maimed Jockeys; A Nationwide Toll,” claimed there was rampant illegal use of drugs in horse racing that caused injuries to both horses and jockeys. The NYT reported from 2009 through 2011 trainers were “caught illegally drugging horses 3,800 times, a figure that vastly understates the problem because only a small percentage of horses are actually tested.” The article cited this as evidence of a state regulatory failure to stop “cheating.”

The NYT’s article prompted another call by some in the industry for federal regulation of horse racing and a ban on all medication, including furosemide (“lasix”) that prevents pulmonary hemorrhaging in race horses. However, an analysis of regulatory data in thoroughbred racing states shows the NYT’s assertions are badly flawed and seriously misleading. Likewise, the call for a medication ban is premised on misconceptions by industry participants, including breeders, who are perhaps putting their wallets ahead of horse and rider health and safety.

According to "The Jockey Club Fact Book" from 2009 through 2011, the average field size in 139,920 Thoroughbred races run throughout the United States was 8.17 horses. Because at least two horses in every race, the winner and another horse selected by the stewards, are routinely tested for drugs 25% of all horses (2 out of every 8) were tested. Statistically speaking, that is a representative sample of all horses racing in the three year period. At the outset it is thus fair to say the NYT was wrong in claiming post race testing “vastly understates” the extent of “cheating.”

What then were the results of drug testing in the NYT’s three-year period? Do they show rampant “illegal drugging”? The answer is a resounding no. Based on data maintained by state racing commissions and compiled by the Association of Racing Commissioners International, 99.26% of nearly 300,000 post race tests were negative for drug use. Those percentages are not by any stretch of the imagination evidence of rampant drug use. They should be the envy of every other sport that tests for drugs.

Horse racing spends about $35 million a year on equine drug testing. The Association of Racing Commissioners International notes the World Anti-Doping Agency, which conducts testing in other sports, in contrast earmarks $1.6 million per year for testing fees. Laboratories conducting testing for the horse racing industry include those at the University of California/Davis, the University of Florida, the University of Illinois, Iowa State University, Louisiana State University, West Chester University, and Morrisville State College. Also involved are private ISO accredited laboratories like Dalare Associates (Philadelphia, PA), HFL Sport Science (Lexington, KY), and Truesdail Labs (Tustin, CA).

Granted in the three years surveyed by the news article, there were positive test results, but only about half the 3,800 claimed by the NYT. Even so, nearly all were for drug concentrations above regulatory levels of permitted therapeutic medication, like common non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (e.g. “bute”) similar to Aspirin, Advil, and Aleve taken by humans. Only a handful of drug test positives (82 out of 279,922, or less than 3/100ths of 1%) were for illegal substances (“dope”) generally having no purpose other than cheating.

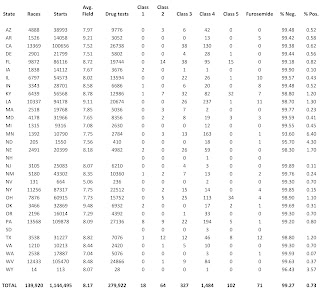

The following chart summarizes the drug testing results for the period 2009-2011. Class 1 and 2 positives are “cheater” drugs or “dope” classified as such by the Association of Racing Commissioners International. Those drugs have the highest potential for affecting performance and have no generally accepted medical use in racehorses. Class 3, 4, 5, and furosemide (“Lasix”) positives, on the other hand, generally indicate overdoses of therapeutic medication. Therapeutics are permitted in race horses and have little or no likelihood of affecting performance. Threshold limits for therapeutics are set by state regulation with the intent that on race day no horse should be under the direct influence of therapeutic medication, except for the permitted race day use of anti-bleeding medication (Lasix).

Racing/Medication Data

2009-2011

(Click here to see this chart larger in a new window or tab)

(Click here to see this chart larger in a new window or tab)

Clearly the above state racing commission data disproves the NYT’s dramatic allegation about the widespread misuse of drugs.

The NYT piece also claims drug use is the main cause of horses being injured and breaking down in races. Based on a purported analysis of Equibase charts the NYT reported an “incident rate” of 5.2 per thousand starts for 2009-2011, which included both quarter horses and thoroughbreds and an expansive definition of “injury incidents.” A subsequent Thoroughbred Times analysis of the same charts found a 4.03 per thousand incident rate for thoroughbreds.

Once again, the facts are other than what the NYT asserted. In 2009-2011, the data shows an overall drug positive rate of 1.8 per thousand starts. Assuming for the sake of discussion the highly doubtful and unsupported premise that all drug use, whether illegal or therapeutic, causes injuries and fatalities the “incident rate” in the three-year period should be closer to 1.8, and not 4.03 or 5.2 per thousand starts, depending on which analysis, if any, is correct. Simply put, the actual data suggests something beside drug use is primarily responsible for racing breakdowns. For this reason, the horse racing industry has been conducting scientific research and analysis on racing surfaces to better understand the role surfaces play in racing injuries in order to further improve the safety of horse racing for both horses and jockeys.

The NYT and many of those industry voices calling for a ban on race-day medication appear to labor under the misconception that race-day medication, in addition to Lasix, is routinely permitted in numerous racing jurisdictions. The NYT says “horses are permitted to run on some dose of pain medication, usually bute.” But that is not true. The “dose” the NYT article hangs its hat on is not active medication, but rather a regulatory threshold limit set for test screening purposes.

For example, in Virginia the current threshold for phenylbutazone (“bute”) is 2 micrograms per milliliter of plasma in post-race testing. On race day, that small concentration has no medicinal effect on a horse, and a test showing that amount or less is regarded as negative. However, the increasing sensitivity of drug testing equipment makes threshold limits like this necessary to avoid having positive test results based upon residual concentrations of therapeutic medication lawfully administered before race day. Or stated another way, “zero tolerance” testing without threshold screening limits will result in false positives.

The NYT compounded its error by implying an increase in racing fatalities at Colonial Downs was caused in 2005 by the Virginia Racing Commission increasing its bute threshold from 2 to 5 micrograms. But a study conducted with the assistance of the Virginia Racing Commission demonstrated there was no statistically significant difference in fatality rates tied to bute threshold levels.

Finally, proponents of a ban on medication point to Britain as an example the United States should emulate. There NYT claims “breakdown rates are half of what they are in the United States [and] horses may not race on any drugs.” None of that is true. According to the British Horseracing Authority (“BHA”), the central body that regulates racing in Britain, the fatality rate in 2011 was about 2 in every thousand starts. In the United States the Jockey Club calculated a 2011 fatality rate of 1.88 per thousand starts. Both rates include steeplechase racing.

Further, horsemen in England are allowed to and do administer the same therapeutic medication used by American horsemen, including bute and Lasix. But on race day, like American horses (except for Lasix) those in England may not compete under the influence of active medication, and like the U.S. the BHA uses threshold screening levels and post-race testing to ensure that is so. The following chart, comparing three years of post-race testing in England (based on the most recent data published by BHA) with the most recent U.S data compiled by the Association of Racing Commissioners International, shows no significant difference in drug positive results between the two countries. Both are essentially drug free.

| Starts | Tests | Negative Tests | Positive Tests | |

| Britain (2006-08) | 286,343 | 27,753 | 99.84% | 0.16% (44) |

| United States (2009-2011) | 1,144,495 | 279,922 | 99.27% | 0.73% (2,066) |

The slight variance between countries may be accounted for by the fact that less than 10% of British starters are tested, while the U.S. tests 25% of all starters, and the U.S. has four times the number of starts. Also, the British select a horse for post-race testing subjectively based on performance in a race or “intelligence” available to the race stewards. In the U.S., selection in each race of two horses for testing is more or less random at the outset. In Britain, only urine is routinely tested, while in the U.S., both urine and blood are examined.

The sole difference in medication policy between the United States and Britain (as well as the rest of Europe) is the use of Lasix. In Britain, Lasix is used in daily training to prevent or lessen pulmonary hemorrhaging, but not on race day. From a horse welfare standpoint that makes no sense. No one disputes that Lasix prevents rather than causes injuries or fatalities in race horses, and thereby protects jockeys as well.

We end by stating our position regarding medication:

A) The National HBPA’s focus regarding medication has always been, and remains, the health and safety of the horse, the safety of the jockey, and the safety of all individuals coming into contact with the horse (i.e. grooms, assistant starters, hot walkers, trainers and veterinarians).

B) The National HBPA believes an independent Racing Medication and Testing Consortium of industry stakeholders, with input from appropriate medical and veterinary professional bodies such as the American Association of Equine Practitioners, should be the final evaluator of medical/veterinary science.

C) RMTC approved medication rules should be considered by the Association of Racing Commissioners International on behalf of state racing commissions, and following a “due process” evaluation with all industry stakeholders being heard, the rules should be adopted or rejected by a majority vote.

D) One of the goals of the RMTC and the ARCI should be Uniform National Medication Rules, which, in turn, should be implemented by means of a National Compact among the states, and not imposed by the Federal Government.

E) Approved Uniform National Medication Rules must be based solely on published scientifically determined regulatory thresholds, with published scientifically determined withdrawal time guidelines, all based on and supported by data published in the scientific literature.

F) RMTC and ISO-17025 accredited laboratories should perform all medication testing.

G) Repeat medication offenders, after “due process”, should be severely penalized, including permanent exclusion from the industry.